Book Review: “The Wild Vine” and the story of Norton

Diversity, as an element in wine appreciation, is one of those “good for you” concepts that almost everyone embraces, but few of us practice. Despite the existence of literally hundreds of different wine varieties in the main wine-grape genus of vitis vinifera, most wine drinkers limit themselves to drinking the same dozen or so varieties—cabernet, pinot noir, syrah, chardonnay, riesling, etc. Even the most adventurous of wine drinkers probably consumes no more than 2 or 3 dozen different varieties on a regular basis. And as for wine grapes that are outside the universe of vitis vinifera, well, those grapes might as well not exist at all. But are we missing something important by limiting ourselves so severely? In failing to appreciate (or even sample) the breadth of expressions available from wines off the beaten track, do we deprive ourselves not only of something pleasing, but also of something important in our cultural heritage?

Diversity, as an element in wine appreciation, is one of those “good for you” concepts that almost everyone embraces, but few of us practice. Despite the existence of literally hundreds of different wine varieties in the main wine-grape genus of vitis vinifera, most wine drinkers limit themselves to drinking the same dozen or so varieties—cabernet, pinot noir, syrah, chardonnay, riesling, etc. Even the most adventurous of wine drinkers probably consumes no more than 2 or 3 dozen different varieties on a regular basis. And as for wine grapes that are outside the universe of vitis vinifera, well, those grapes might as well not exist at all. But are we missing something important by limiting ourselves so severely? In failing to appreciate (or even sample) the breadth of expressions available from wines off the beaten track, do we deprive ourselves not only of something pleasing, but also of something important in our cultural heritage?

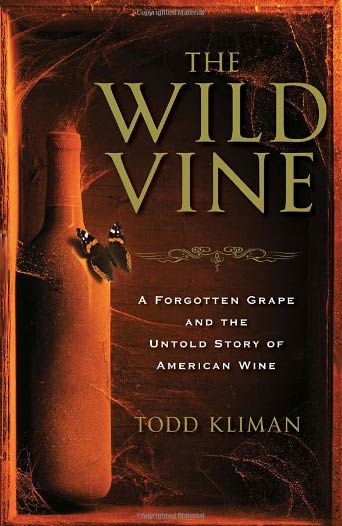

These thoughts kept going through my mind as I read The Wild Vine: A Forgotten Grape and the Untold Story of American Wine, author Todd Kliman’s paean to the Norton grape. But the book is not a dry, technical description of the grape’s discovery and evolution, nor is it a tasting guide. Instead, it is a history of a specific fragment of wine making in America, viewing it through the earliest efforts of the Jamestown colonists, the dedicated efforts of America’s greatest early wine advocate Thomas Jefferson, and on to the rise of the wine industry in Missouri, the center of American wine industry before California began to rise in importance in the final decades of the 19th century. In telling the history of the Norton grape, Kliman reveals a fascinating slice of American history that places wine as a significant cultural element in both early American history, and in the expansion of America into the Midwest and beyond by wine-loving German immigrants in the mid-1800’s. The result is an appreciation of wine’s significance in America that predates the much better known history of California’s wine industry. Although the efforts of the early missionaries and other wine growers in California are usually thought to be the beginning of serious wine cultivation in America. Kliman’s book documents a significant part of the history of wine making in America before California took over the stage.

Some of what Kliman describes is fairly well-known, in particular the efforts of Jefferson to create vineyards modeled on France using European vitis vinifera varieties. Less well-known, however, is the discovery (or perhaps the invention) of the grape that became known as Norton’s Virginia Seedling by Dr. Daniel Norton in the early 1820’s. The origins of the grape are murky, and this book does not contain any breakthrough information on its origins. What is known is that Dr. Norton was experimenting with hybridization when he attempted to pollinate an early variety (ironically named “Bland”) of the native American genus vitis lambrusca with the pollen from a European variety, probably Petit Meunier. However, he did not isolate the flower, so pollen from another native American grape genus known as vitis aestivalis may have impregnated the plant, blurring the resulting grape’s true origins. However created, the grapes were vigorous enough to withstand American winters, and were resistant to mold and other maladies associated with the humid American summers, while not containing the “foxy” flavors that rendered most native American varietals unpleasant to the taste.

After tracing Norton’s (i.e., the grape’s) early history and success, the scene shifts to Hermann, Missouri, where German immigrants create a wine industry that dominated the American wine scene immediately before and after the Civil War. Norton played a significant role in the success of the industry in Missouri (as it does to this day). Kliman documents how the Norton grape came to be seen as America’s greatest indigenous varietal, and one of its most successful on a commercial level as well, culminating in a wine from Missouri’s most highly regarded winery (now known as Stone Hill) being awarded a gold medal at the International Exhibition in Vienna in 1873. Bookending the stories of Norton’s beginnings in Virginia and its success in Missouri is the story of modern-day Norton champion Jenni McCloud of Virginia’s Chrysalis Vineyards, who today has the nations’ largest planting of Norton and is one of the top producers on a qualitative basis as well. The descriptions of her passion for Norton, and her winemaking and business success with the variety, juxtaposed with her frustration in expanding Norton’s acceptance even among her fellow Virginia winemakers, makes for a compelling story.

Kliman is an excellent writer, and he interweaves his narrative with interesting historical references that help contextualize Norton’s place in American viticultural history. Although Kliman occasionally makes it appear that Norton is far more central to American wine industry than it appears to be today, he uses historical events to try to understand or explain Norton’s relative obscurity among America’s wine lovers. The role of immigrants in America, the impact of the transcontinental railroad, and the devastation wrought by Prohibition are all discussed and illuminated through the lense of Norton’s struggle for acceptance. Historians may argue the relevance or significance of Kliman’s conclusions, but his reasoning and writing are persuasive. Yet his obvious enthusiasm for the grape and the wines it makes obscures what should be a key element in its success, or failure: does it taste good? A comment he attributes to a prominent Virginia wine consultant and writer sums it up: “There are some who like it, a few who love it, and many more who loathe it. It’s really a kind of love-hate thing.” In matters of taste, it would seem, all of the colorful history and cultural significance one can muster are simply not enough to ensure success.

Kliman is an excellent writer, and he interweaves his narrative with interesting historical references that help contextualize Norton’s place in American viticultural history. Although Kliman occasionally makes it appear that Norton is far more central to American wine industry than it appears to be today, he uses historical events to try to understand or explain Norton’s relative obscurity among America’s wine lovers. The role of immigrants in America, the impact of the transcontinental railroad, and the devastation wrought by Prohibition are all discussed and illuminated through the lense of Norton’s struggle for acceptance. Historians may argue the relevance or significance of Kliman’s conclusions, but his reasoning and writing are persuasive. Yet his obvious enthusiasm for the grape and the wines it makes obscures what should be a key element in its success, or failure: does it taste good? A comment he attributes to a prominent Virginia wine consultant and writer sums it up: “There are some who like it, a few who love it, and many more who loathe it. It’s really a kind of love-hate thing.” In matters of taste, it would seem, all of the colorful history and cultural significance one can muster are simply not enough to ensure success.

Perhaps this is why my take on the overarching theme of The Wild Vine is the celebration of diversity for its own sake. Mixed with the American trait of rooting for the underdog, Kliman has written a valuable tale of perseverance and individuality, with a uniquely American slant. It seems unlikely that this book, or any other, will generate significantly more interest in the Norton, or its acceptance as a “serious” wine grape on the same plane as European varietals, but this is a thoughtful and passionate argument for diversity and for the cultural significance of at least one uniquely American wine, presented as a beautifully written drama. I highly recommend the book for anyone with an interest in American history, or wine of any kind.

As I was reading this book, I realized that although I like to flatter myself as being a fairly open-minded and adventurous wine lover, I couldn’t recall ever tasting or drinking a Norton wine myself. While it’s possible I had sampled one on a trip back East, the fact is that Norton is virtually unobtainable in California without an extensive search. So I decided to order a few of what I hoped would be the best, or at least the most typical, Norton wines I could find directly from the wineries that produced them. Two of the wineries whose wines are purchased are prominently featured in the book, and the third is one that seemed to get some good notices on various Norton-related web postings I had found. The seven bottles I sampled gave me a pretty good idea of Norton’s appeal, and perhaps it’s limitations as well. I opened these for my wine-tasting group, as none of us had really explored Norton previous to this. First, the notes:

2003 Chrysalis Norton (Virginia, 12.8% alc., $19). Nice ripe berry nose with black fruit, plums, Asian spices. Bright acids on the palate, cranberry with some animale notes and herbs. Medium bodied with very low tannin, smooth and round with lingering acidity in the finish and a hint of citrus. Very fresh with little apparent development, but good balance even if lacking tannic grip.

2005 Chrysalis Norton (Virginia, 12.8% alc., $16). Deeper nose than the ’03, with a touch of vanilla. Riper, with slightly lower acid although still on the tart side, but seemingly better balanced. Quite spicy with a garrigue-like aromatic note. Low tannin, a touch of earthiness and pine needle with good length. Very clean and pure.

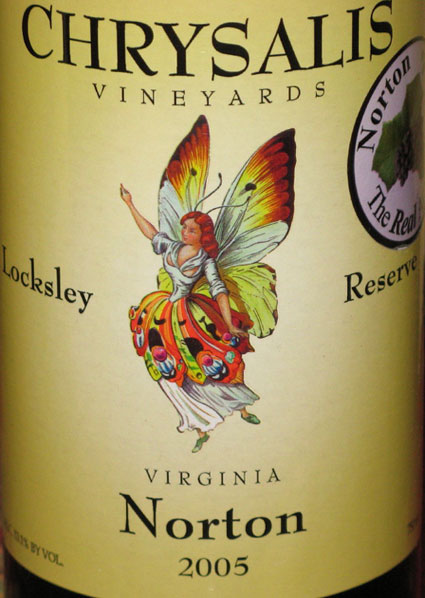

2005 Chrysalis Norton “Locksley Reserve” (Virginia, 13.1% alc., $35). Even deeper and riper with black fruits. More acidity than the regular 2005, fairly rich and spicy with distinct citrusy flavors plus pomegranate, plum and baking spice. Low tannin, long, not oaky. While a bigger, riper wine than the regular 2005 bottling, it’s a bit clumsy by comparison, and I actually preferred the regular to this reserve because of its better balance and fresher aspect.

2003 Stone Hill Norton (Missouri, 13% alc., $30). Somewhat funky nose with some barnyard and earth. Red fruits on the palate intermixed with the barnyard scents that add a musky element without overwhelming the fruit. Bright, very high acid and tart fruits, almost too much so, giving a distinctly citrusy feel. Moderate but smooth tannins. A bit skinnier than the Chrysalis wines, but similar flavors and structure, and reasonably well balanced.

2006 Stone Hill Norton (Missouri, 13.8% alc., $19). A touch of what could be TCA on the nose. Very tart with a musky note, bright, citric and acidic. Air increases the musty component and I quickly conclude the wine is corked. Seems like a similar wine to the 2003 before the TCA overwhelms it.

2007 Stone Hill Norton, “Cross J Vineyard” (Missouri, 13% alc., $25). Very intense bright berry fruits on the nose, reminiscent of a Beaujolais Nouveau. Delicious fruit full of berry/strawberry/cranberry flavors, very effusively fruit-forward. Brisk acidity and low tannin, the flavors simply delicious and much more direct than the previous wines. A Beaujolais-style of Norton, and a good one. The first bottle to be finished by my group.

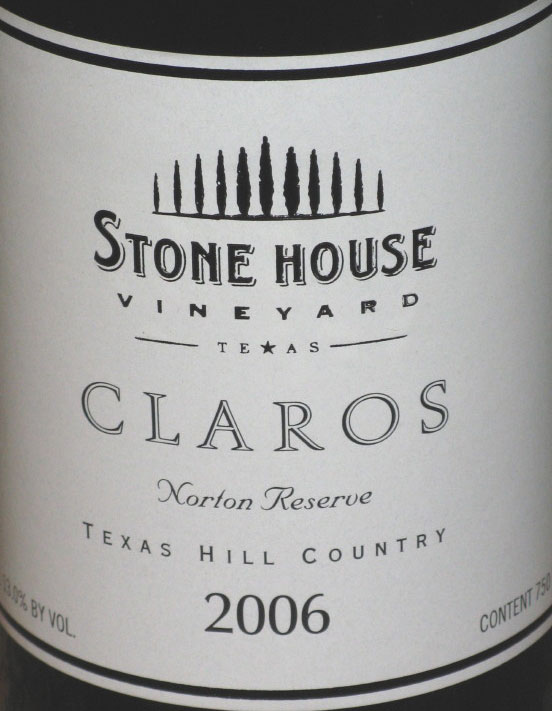

2006 Stone House “Claros” (Texas, 13%%, $25). Quite ripe on the nose with a bit of VA, funky/barnyard but not overwhelmingly so. Very high-toned acidity that seems a bit volatile, giving a sharp and warm impression to the wine. Some leafy/herbal flavors with both red and black fruits, especially cranberry and plum, with a note of citrus. Very strong acid, just a little tannin, but the volatile notes give a disjointed aspect to the wine, which seems clearly to come from a warmer climate. Find this wine

Overall, I was pretty well pleased with these wines, and found them to be enjoyable. Describing their flavors in a tasting note isn’t easy, and I found myself grappling for comparisons with wines (mostly European) I had greater familiarity with. In general, I would describe Norton as tasting like a hypothetical blend of a traditional Italian Barbera (with its tart acidity and low tannin) and a Southern Rhone wine from an appellation like Listrac or a Cotes du Rhone villages, with the bright cherry and savory herbal notes mixed with a bit of barnyardy funk. There can be a hint of something of the taut structure and herbal notes of a crisp Loire red (either Gamay or Cabernet Franc) in the mix as well. The wines are most definitely “food wines,” in the sense that their high acidity would be very refreshing and palate-cleansing at the table, but perhaps a bit too much if sipped on its own. My wine group seemed fairly pleased with the wines, but most described them as “interesting” as opposed to the kind of wines they would actually seek out and drink at home. But we all concluded that the wines were well-made and food-friendly, and certainly offered more interest than much of the mass-produced vinifera wines that fill the shelves of most stores today.

However, the high acid/low tannin profile of this wine flies in the face of the preferences of the most prominent critics and writers today, which tend to favor lower acid, higher tannins wines of greater richness, density, and extract. So getting broad acceptance of the wines faces an uphill battle. And maybe the name “Norton” is just too ordinary and dull sounding to entice people into giving the wine a chance? It’s funny, most the friends that I told that I was reading a book about Norton responded with some variation of a joke referencing “The Honeymooners”/Ralph Kramden/Ed Norton (“Hey, you gonna taste any Kramden wines with those Nortons?”). For my generation, it may be hard to take seriously a grape that is associated with a fictional character who worked in the New York City sewers. But it would truly be sad if such silliness, or critical apathy or hostility, stood in the way of Norton’s broader acceptance. It may not produce the greatest wines made in America, but it deserves a place at the table.

Related posts:

Enjoyable article that not only reviews a wonderful tale of a grape and its wine, but more properly goes the next step in tasting the thesis of The Wild Vine. 184 Norton/Cynthiana vineyards today in 22 states. Some Norton wines we have enjoyed by state: Three Sister (GA); White Oaks (AL); Century Farms (TN); Elk Creek (KY); Cooper (VA); Stone Mountain Cellars (PA), Blumenhof, Heinrichshaus, Chandler Hill, & Robller (MO). Remember, all Nortons, which should be considered an acquired taste wine, have to breathe at least 30 minutes or longer before properly tasting.

Hi Bennett,

I am from Missouri and have lived here all my life yet drink no MO wines. When in wine country I try them, and of course I wish desperately that there were good wines made so that I could enjoy trips to what are really some lovely wine areas in this state, and in the general spirit of locovorism and home-state pride as well. Hermann is still a very nice spot to visit and is a regular day trip by train for those in the St. Louis area. But most of the wine consumed there is sweet v. lambrusca whites (or hybrids quite often) made in a style imitative of the Germanic origins of the region, but lacking much character beyond cloying sweetness. One problem with assessing the Norton quality has always seemed to me to be pricing which I find far too ambitious when compared to what is available on the market. This is true in the state’s other wine areas as well.

Overall my samplings of Norton have shown much of what you describe, an almost bizarre-seeming lack of structure, at least when compared to conventional European varietals. I am intrigued by your note on the Stone Hill Cross J and would give it a try, but again think of all the excellent beaujolais available for $25/btl.

All in all I just watch the state’s efforts with vinifera more closely. Perhaps with modern farming technique we could see some efforts that will withstand the more hostile climes of this rather extreme state. The attempts are being made, but in the meantime I’ll attempt not to completely ignore the Norton.

Thanks Marshall. I tasted the Lousiana wine you brought, the Ponchartrain Norton/Cynthiana, after the main group when I was already in party mode, so I didn’t take notes, but I recall thinking it was qualitatively comparable to the others. It’s intersting that in Louisiana, and also apparantly Arkansas, Norton is often labelled as Cynthiana. Although they were long thought be be related but different grapes, I read somewhere that genetic testing showed them to be the same, although perhaps different clones. Anyway Ponchatrain is apparantly another highly regarded grower of Norton. I liked it.

Very nice article and extremely interesting tasting. I was glad to partake and I felt the Norton’d matched well with the grilled tri-tips. No mention of the Louisiana wine?? I am inspired to read the book!

RT @gangofpour: Book Review: "The Wild Vine" and the story of Norton http://bit.ly/dasvxz #wine

Nice read, Bennett, thanks for the report. I think I’ve tried a Norton once, but I can’t tell you where or when; obviously, that one wasn’t particularly memorable. I’ll have to try it again and pay a little more attention next time!

Book Review: "The Wild Vine" and the story of Norton http://bit.ly/dasvxz #wine